Cozy web

Building a space for creativity that feels safe, warm, and a little messy

You know those moments that stick with you and randomly popup every few years? Sometimes they’re wonderful, welcome memories. Other times, they’re awkward moments that your brain insists on replaying for seemingly no reason other than to make you cringe.

One of those cringe moments for me is from 2017, when I started a new job and was introduced at a company All Hands meeting. To my horror, the quirky CFO had made a surprise slide with screenshots of my very first Tweets (long since deleted).

They weren’t offensive or even personal. Just random updates from 2008, like “So much homework to do, but I’m soooo sleepy.” (I was in grad school at the time.) Still, standing in front of my new coworkers, I thought: what kind of person posts inane life updates on the open internet these days?

It was surprising how much my own internet habits had shifted, and, as I reflect upon that experience today, how much they’ve continued to shift. Posting feels very different now (see my recent post on ambient intimacy).

This evolution of what we share, and in what venue, has led to a few theories.

Dark forest theory

In 2019, Kickstarter co-founder Yancey Strickler shared an essay called The Dark Forest Theory of the Internet. Despite being distributed via a ”closed” email newsletter, it ironically went semi-viral.

It’s a short read (or you can watch 0:51-4:49 of this video), but here’s the gist:

The Fermi paradox asks why we haven’t found alien life despite there being many reasons to believe it could exist (scientifically speaking). Sci-fi author Cixin Liu’s twist on it, the dark forest theory of the universe, suggests maybe non-human intelligent life has chosen to stay quiet, like animals in a forest at night, to avoid predators. So the silence should not be conflated with evidence of absence.

Strickler applies this theory to the internet: in response to ads, tracking, trolling, and other predatory behavior, many people have retreated from the visibility of the “clear net” (Instagram, TikTok, Twitter/X, etc.) into safer, private spaces, like group chats, podcasts, newsletters, and forums. And he believes the clear net “public square” has grown quieter and more synthetic as true discourse continues in the shadows of the internet.

When I first heard of this theory via a video interview, I was intrigued, but as I digested it a bit, I had a few visceral reactions.

First of all, as a friend and YouTube commenters savvily pointed out: a forest is actually pretty loud at night! And, like, of course there’s a difference between public and private life, which has been the case since at least ancient Greece, so it’s unsurprising that online spaces mimic this fundamental offline construct. And there’s still bustling activity in the public internet. We get glimpses of shared, mainstream experiences now and again, like when the Coldplay kiss-cam mishap briefly unified the masses with memes, or when we all got pope-pilled. Bubbles can burst, people can be real online—and funny!

The forest isn’t completely dark.

But I also get what he’s saying.

Case in point: those boring Tweets I naively blasted into the world. They resurfaced to embarrass me years later, a harmless example of how public posts can linger. No wonder people retreat. I certainly have (with some exceptions).

But choosing to be silent is rarely benign. Strickler himself noted the risk of “underestimating how powerful the mainstream channels will continue to be, and how minor our havens are compared to their immensity.”

And, as a friend rightfully pointed out, retreating from the public online sphere to closed spaces can just be excuses for people to behave badly, without fear of consequence.

Still, I think there’s a more innocent reason people “go dark” (or have a “Close Friends” list on social media platforms): to escape the pressure to share only polished, exciting life updates. Because the once public, vulnerable discourse of the early internet has been converted to performative content creation that’s commonly manufactured to sell something or otherwise “manipulate attention”.

And when you’re dabbling in creative expression, the open platforms reward the perfect finished product, and not the messy, dilly-dallying path that you took to get there. And you may not want your half-formed ideas or experiments immortalized in the algorithmic firehose of the clear net. Or even worse: on an All Hands slide!

Reducing that risk and celebrating the mess are some of the many reasons why we are so excited about Practice. But more on that in a minute.

Cozy web

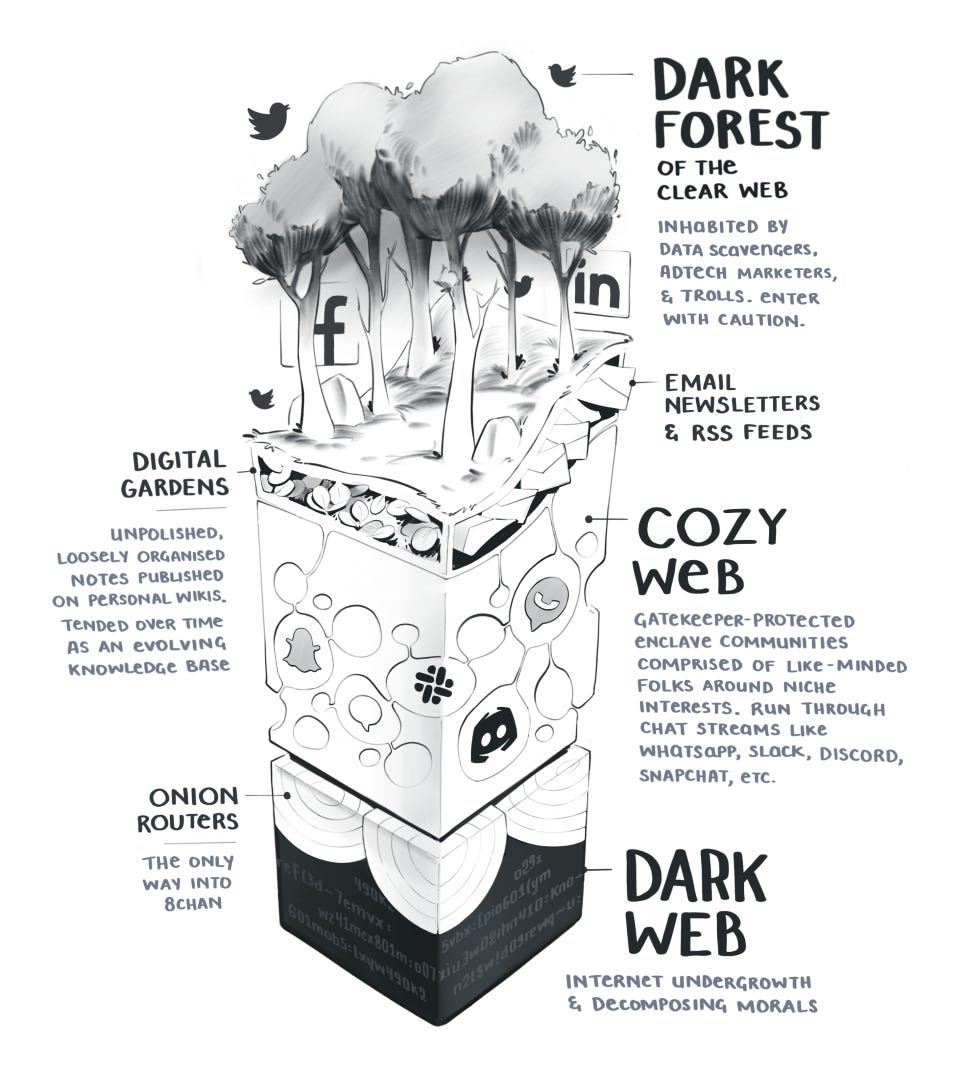

In response to Strickler, writer Venkatesh Rao mapped his own view of the internet and coined the term “cozy web” to describe its private corners where gatekeepers create a safe space for connection. A few days later, Maggie Appleton wrote a follow-up to the two essays1, entitled “The Dark Forest and the Cozy Web” which she illustrated with the following sketch:

In her essay, she further described the cozy web as:

“…tiny underground burrows of Slack channels, Whatsapp groups, Discord chats, and Telegram streams that offer shelter and respite from the aggressively public nature of Facebook, Twitter, and every recruiter looking to connect on LinkedIn.”

She also illustrated a layer between the cozy web and the clear web: digital gardens. Where people share “unpolished, loosely organized notes.” There is an implied puttering around in that digital garden, perhaps while sipping on a cup of tea. And much like the the cozy web, there’s an element of raw vulnerability and authenticity.

Both are slices of the internet that, unlike the dark forest of the clear web, are filled with realness and warmth. Coziness.

Getting cozy

My friend Annie (who shared the dark forest theory with me) suggested we think about the cozy web while building Practice, since we’re “building a new kind of platform for creativity.” And she’s right.

Because we do want Practice to feel cozy.

We’re creating something that’s more robust and structured than a Discord server or Slack channel, so I’m not sure it’ll feel quite as cozy as what Appleton sketched out. But we do want to create a space that feels safe from trolling and judgment, yet also invites sharing (which is no small feat!).

We want to encourage people to capture all parts of their creative process, even when they’re stuck or frustrated. It means valuing honesty over performance: messy middles, cluttered workstations, failed experiments…not just glossy finished pieces.

It also means some gentle gatekeeping. We want diversity and openness within the Practice community, but we also want participants who are serious about experiencing joy through making. Not lurkers or silent spectators, but people who want to show up, share their practice, and support others.

Because we don’t want to create another dark forest.

We want to create a place where creative making feels like self-care. A place that feels cozy. And alive.