Recently, a friend was giving me feedback on Practice and said: “An annoying thing: is there a better way to say ‘creative hobbies’?” I assured him he wasn’t being annoying (feedback is a gift, remember?) and he clarified:

I responded with an emphatic, “IT IS!!!” But he had a point.

“Hobby” origins

My friend’s comment was not the first time I’ve heard, observed, or read some disdain or hesitation about the word hobby. Let’s take a look at the definition to try to unpack this perception:

Nothing too surprising, but we all need to take a moment to appreciate the archaic definition of “hobby” which led me to the etymology of the word:

The word hobby originally referred to a small horse or pony. It later came to mean a toy horse, or hobby horse, and eventually evolved to mean "an activity done for pleasure" (source)

From ponies to toys to pastimes. A bit tangential, but I love it!

Okay, back to the point of this dictionary spelunking. The modern definition of “hobby” is: “An activity done regularly in one's leisure time for pleasure.” Leisure time? Who has time for that? Pleasure? How indulgent. Next thing you know, you’ll be prioritizing joy in your life. Or competing in a hobby horse championship. Grow up! 😉

I’ve been whining writing about how creative hobbies—and other forms of creative expression, especially when done for fun, not profit—aren’t seen as valuable pursuits, despite being a drug-free “wonder drug” that’s scientifically proven to reduce cortisol levels, stimulate neuroplasticity, trigger flow states, and create balance in the autonomic nervous system, among other benefits. I’ve outlined a few hypotheses about this value perception in prior posts, but the tl;dr is that it’s no surprise that, in 2024, the broader term hobby feels low-value and gives the ick to some people. Even its delightful equine roots won’t change the fact that having a hobby in 2024 feels inherently frivolous.

What makes something “creative”?

While we’re dissecting word choice, we should probably also poke creative with a stick. Many of the hobbies we’ve seen in scientific studies and that we’ve included in our initial Practice Hobby DNA aren’t “creative” in the strict sense, according to our new BFF, the Oxford dictionary:

Building LEGO sets, completing a diamond painting, stitching an embroidery pattern—all are definitely Practice hobbies, but they aren’t based on the hobbyist’s “imagination or original ideas.” According to Danish psychologist Dr. Anne Kirketerp, these are examples of “recreative” hobbies, where the hobbyist follows instructions or patterns rather than creating something from scratch. They are highly structured and prescriptive, though hobbyists may personalize their projects through choices like color selection or modifications.

This is not a value judgement of those hobbies or projects. There’s absolutely zero shame in following instructions as part of your re/creative practice. Doing so can be restorative, soothing, and deeply satisfying. The results can be stunning. Many projects that are recreative, like following a complex knitting pattern, require a high level of skill and years of practice. But are they, by Oxford’s definition, creative? Not technically.

Then there’s the connotation of being a creative (the noun). Ben and I believe every human is inherently creative, and we want to eliminate any gatekeeping of that label. But we also are concerned that “creative” may be alienating to those who are early in their Practice journey or otherwise don’t perceive themselves that way.

So maybe creative isn’t the best word to use either? Shoot.

Maybe “Craft” can work?

We’ve considered using the word craft, but it has its own stigma. Craft is defined by the Oxford dictio—JUST KIDDING. But the word “craft” has it’s own interesting history and implications.

Craft used to be an essential part of daily life—people had to make their own clothes, tools, and household items. Over time, and particularly after the Industrial Revolution, craft became less of a personal necessity and more associated with decorative work.

The Arts and Crafts movement of the late 1800s/early 1900s was, in part, a reaction against mass-produced goods. Its advocates wanted to preserve the skills and role of craftspersons as machines increased the scale of production and access to jewelry, furniture, and other previously handmade items, all while bypassing traditional makers. One of the most well-known voices and makers of the Arts and Crafts movement, William Morris, said, “Without dignified, creative human occupation, people become disconnected from life.”

I think parts of this movement still resonate today. In some ways, Practice is Arts and Crafts 2.0 in that it intends to elevate the role and perception of craft in modern life and get more people making things with their hands. And feeling loosely connected to the Arts & Crafts movement is kind of exciting, because it was rather successful in making craft more revered and mainstream in early 20th century Britain (#goals). But we also have our differences: Practice’s goal is to use craft to reduce burnout and create joy, and we embrace—rather than reject—technology.

Morris’ critique of Industrial Revolution-era technology—which he believed created too much distance between the designer and the act of manual creation—got me thinking about the current gripes surrounding the role of generative AI in art and creative expression. Unsurprisingly, I was not alone and a search for “generative AI arts and crafts movement” led me to many essays on the topic. I particularly liked this one by Krzysztof Pelc on Wired, where he talks about “the William Morris effect” and proposes: “Time and again, technical advances change our sense of what is appealing or valuable.”

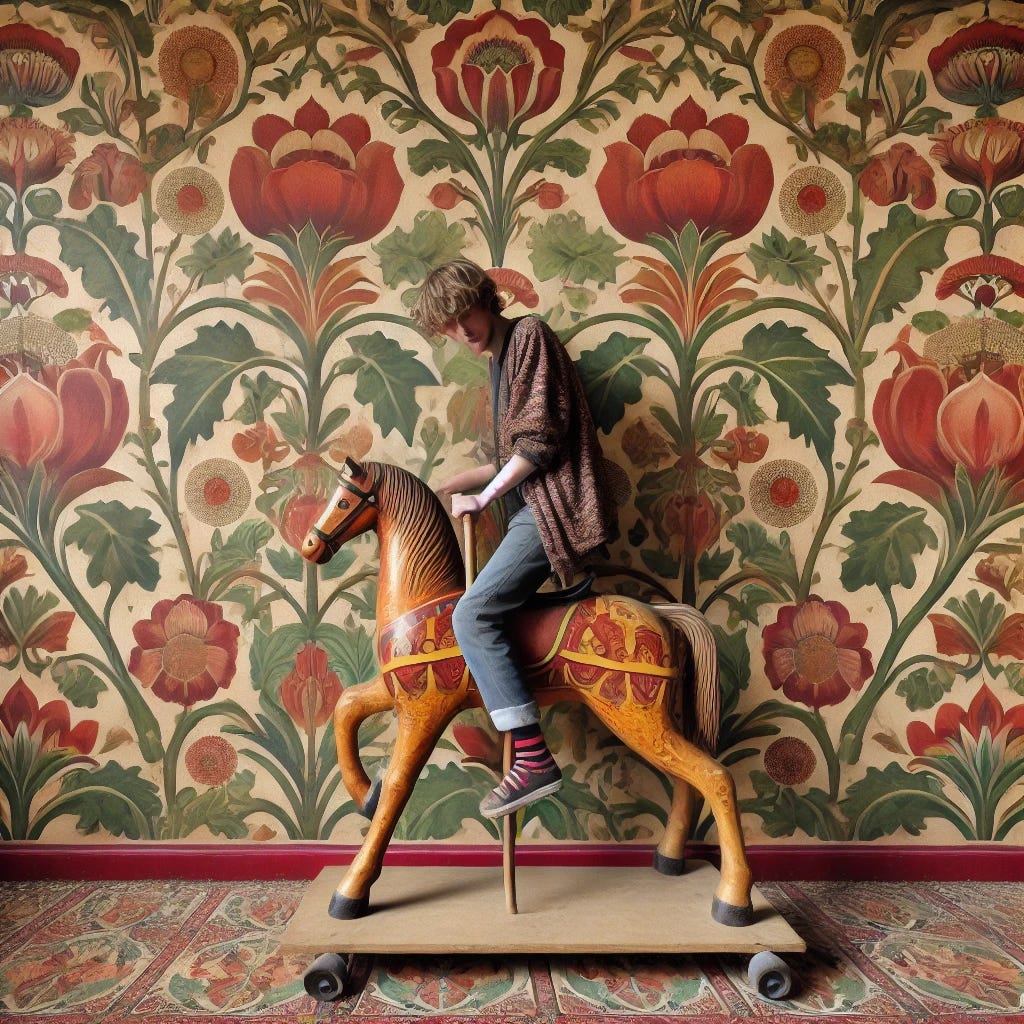

I am confident that William Morris would be APPALLED by generative AI. What if I told you, dear William, that while laying on my bed, surrounded by mass-produced goods, eating bonbons, I can pick up a handheld device connected to all the world’s information and request “an image of someone riding a hobby horse over a background of William Morris-style botanical wallpaper”, and bleep-bloop: out pops a horrifically haunting image of a blurry-faced person on a carousel horse.

It’s a bit morbid, but I imagine Mr. Morris seeing this image and hearing how it was made, and him responding by rolling over in his beautifully wallpapered, hand-carved coffin.

Despite Morris’ seemingly prescient concern and the impact of the Arts and Crafts movement, craft is still largely seen as non-essential and decorative today.

Arts vs. crafts

Speaking of Arts and Crafts, let’s continue on this esoteric journey and explore the distinction between Art (with a capital A) and craft. Art is expected to have meaning, conceptual implications, and create societal discourse, whereas craft is often seen as simply ornamental and pretty—and (erroneously, IMO) not seen as the carrier of a message. I came across a piece called Rethinking our Perspective: The Value of Craft within the Culture of the Traditional Art World, which described the relationship between art and craft as follows:

Craft is a medium of cultural expression as powerful and worthy of attention as painting, sculpture, or architecture. However, crafts are often considered an inferior art form and overlooked in favor of more conventional art forms.

This hierarchy was evident in my undergrad art education, not only as a pedagogical undercurrent but also symbolically in our art building, where craft disciplines like printmaking and fiber arts were relegated to the basement, while the painting and drawing studios were on the top floors.

Even my grad school, California College of the Arts (CCA), used to be called CCAC, or California College of Arts and Craft. They chose to drop the C in 2003 after nearly 100 years of existence because “the college's governing bodies have decided that the institution's range of programs, curricular and public, has long since outstripped its founders' sense of mission and that ‘arts and crafts’ no longer expresses the distinctions among creative disciplines.” (source) But some students, faculty, and alumni were not pleased by this choice, interpreting it as a de-prioritization or de-valuing of crafts versus fine Art and design.

And back to the article:

Historically, art has been associated with the elite and high culture, while craft has been related to the lower classes and the traditions of local cultures…The distinction between art and crafts results from the structural barriers, prejudices, and stereotypes that exist in our society and impact artisans and craftspeople.

A bit heavy, but I don’t disagree! It’s also hard to ignore that craft is historically associated with women and domestic work, which means it hasn’t exactly been highly regarded in modern Western society (not to blame the patriarchy or anything). Lots more to say about this, but given how long this post is already, I better move on.

So yeah, “craft” may not be the best word for us to use either.

Words are hard!

Welp, we’ve used the terms “creative making”, “creative hobby” and “craft” somewhat interchangeably when describing Practice. But those words have baggage and may be technically imprecise. So how else should we describe the 30+ activities we support and want to introduce folks to? Is there an umbrella term that encompasses both high-structure and low-structure, recreative and creative activities? One that has less stigma than “craft” yet is inclusive of building, stitching, assembling, shaping, carving, and more? Is it simply “using your hands”? Is it “practice”? Or a word that we either repurpose or invent?

As you may have gathered, we’re still figuring that out.

We’ve somewhat unintentionally set the goal of changing how people perceive [creative hobbies] or whatever word(s) we choose. We want to destigmatize [creative] and recreative [hobbies], making them something seen as good-for-you and essential, because we know that [creative making] has the potential to change lives.

We’ll probably just stick to the words creative, hobby, and craft, acknowledging and accepting their imperfections. Maybe we add the goal of changing the perceived value of these words as part of our to-dos? Post-MVP, of course!

Any linguists out there have thoughts on our word choice? Leave a comment below or email me your ideas at: erica@practicemaking.com

I've been following a lot of people in the 'Maker' community on YouTube for years and always liked that as an inclusive term for a wide range of hobby/craft/builder/whatever it may be, though have never thought about it very critically.